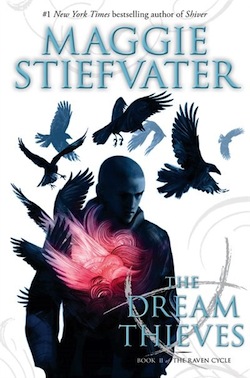

Continuing from the last installment. Having finished reading Maggie Stiefvater’s Raven Cycle for the second time in the course of a month—and if we’re being honest, I think it was less than a month—I feel like it’s high time for me to write about the experience. Because I loved it. I mean, I loved it.

The significant thing about The Dream Thieves—Ronan’s book, in many ways—is that it’s one of the best actual representations of queer experience and coming to terms with one’s sexuality that I’ve ever had the pleasure of reading. The focus on recovering from trauma and forging a functional self out of the wreckage, too, is powerful—not just for Ronan, but for his companions as well. It works because it isn’t what the book is about; it’s something that happens during and across and spun into the things the book is about. There’s no signposting of “hm, I am gay”—it’s all about feeling, experience, the life that moves around you while you realize who you are one thread at a time, in perhaps not the most healthy or recommended of ways.

I’ve felt the most attachment to Ronan for a variety of reasons—having been one myself, it’s hard not to spot a kindred spirit—but predominant among them is that Stiefvater writes his eccentricities, his hyper-masculine tendencies, his raw broken intensity, with such care and attention. It isn’t enough to tell me that a character drinks; that he has some issues with loss and communication; that he needs to get out of himself with fast cars and faster friends and danger; that he’s running from something in himself as much as the world around him—show me.

And she does. Same with his burgeoning sexuality, his secrets from others and himself, his attraction to Adam and Kavinsky in equal and terrifying measures. It’s “moving the emotional furniture around” while the reader isn’t looking, as she’s commented before about her prose style, and it works amazingly well. His struggle with himself could so easily be an Issue Story, or he could be a Typical Badass Dude, but neither of those happens.

Ronan Niall Lynch is just a guy, and he’s a guy with a lot of shit to work out about himself. I sympathize. Most of this essay is about to veer off into the territory that struck me most, reading the novel again, and that’s all about Ronan and Kavinsky. There are a thousand other spectacular things happening here—between Adam and Blue, Adam and Gansey, Gansey and Blue, everyone and Noah, and also the adults—but there’s a central relationship outside of the fivesome that makes this book something special.

The aesthetic between Ronan and Kavinsky hovers in the neighborhood of: Catholic guilt, street racing, cocaine, personal emptiness, raw unpleasant intense relationships, being complicated and fucked up together. Failure to communicate. Failure to connect, acting out as a result. I could write a dissertation about the relationship between these two; I’ll try to narrow it down. There’s a tendency to underwrite Kavinsky in the fandom discourse—or, equally frustrating, to cut him far more slack than is safe or healthy. It’s odd to call a character who does things like scream “WAKE UP, FUCKWEASEL, IT’S YOUR GIRLFRIEND!” at Ronan subtle, but: there we have it. I’d argue that Stiefvater’s building of his character is as subtle and careful and brilliant as anything; it’s just that it’s easy to miss in the gloss and noise and intensity of his persona. Ronan, in fact, often does miss it—and we’re mostly in his head, but we’re capable as readers of understanding the things he fails to parse when he sees them. It also allows us to see Ronan—all of him, good and bad—far more clearly than we ever have before.

He’s the most complex of the raven gang, I would argue, because of this: his life outside of them, without them, where he does things that aren’t all right. There are implications aplenty in the scenes with he and Kavinsky alone together, as well as in their constant through-going interactions (the aggressive gift-giving, the texting, the racing), of the things that Ronan keeps from Gansey and the side of the world he thinks of as “light.”

Because there’s antagonism, between them, but it’s the kind of antagonism that covers over something far closer, more intimate, and more intense. It’s an erotic exchange, often, distinctly masculine and sharp; Ronan himself, with the smile made for war, is filling some part of himself with Kavinsky that is important to him. The complex tension between these two young men reflects a lot of self-loathing and rage and refusal to engage with feelings in a productive manner. I’d point to the text messages, the careful cultivation of disinterest or the performance of aggression—offset by the volume of them, the need of them. It’s flirting; it’s a raw and horrible flirting, sometimes, but there’s no mistaking it for anything but a courtship. Keep it casual, except it’s anything but.

From the early scene in Nino’s where Kavinsky gifted Ronan with the replica leather bands and then “slapped a palm on Ronan’s shaved head and rubbed it” as a farewell, to their race later on where Ronan tosses the replica shades he’s dreamed up through Kavinsky’s window, observing after he wins and is driving away, “This was what it felt like to be happy,” there’s a lot of buildup. However, as Ronan is still living with his “second secret”—the one he hides even from himself, the one that can be summed up with I am afraid—it’s all displaced: onto the cars, onto the night, onto the adrenaline of a fight.

Remember: our boy is a Catholic, and it’s a significant part of his identity. We might get lines about Kavinsky like,

He had a refugee’s face, hollow-eyed and innocent.

Ronan’s heart surged. Muscle memory.

—and we might get them from the start, but it takes the whole journey for Ronan to get to a point where he can admit the tension there for what it is. He does the same with his jealousy of Adam and Gansey in the dollar store, later; Noah understands, but Ronan himself has no idea why he’s so livid that Gansey’s voice might change when Adam calls on the phone, why it’s too much to see Gansey as an “attainable” boy.

All of this, of course, comes to a head after Kavinsky and Ronan fall finally into each other’s company without Gansey to mediate—because Gansey has left Ronan behind to take Adam to his family’s gathering, and Ronan does things that come naturally to him without supervision. The two spend the weekend together in a wash of pills and booze and dreams, the climax of which is chapter 44: dreaming the replacement for Gansey’s wrecked car.

The first attempt is a failure; however, when Ronan is upset, Kavinsky makes a fascinating attempt to comfort him—first by saying, “Hey man, I’m sure he’ll like this one […] And if he doesn’t, fuck him,” and then by reminding Ronan that it took him months to perfect his dreamt Mitsubishi replicas. When Ronan is determined to try again, Kavinsky feeds him a pill:

“Bonus round,” he said. Then: “Open.”

He put an impossible red pill on Ronan’s tongue. Ronan tasted just an instant of sweat and rubber and gasoline on his fingertips.

A reminder that these are the smells that Ronan has earlier commented he finds sexy; also, if the tension in the scene isn’t clear enough to the reader, Kavinsky then waits until Ronan is nearly passed out and runs his fingers over his tattoo, echoing the earlier sex-dream. However, when he dreams the correct car, he immediately tells Kavinsky he’s leaving to return it to Gansey, and:

For a moment, Kavinsky’s face was a perfect blank, and then Kavinsky flickered back onto it. He said, “You’re shitting me.” […] “You don’t fucking need him,” Kavinsky said.

Ronan released the parking brake.

Kavinsky threw up a hand like he was going to hit something, but there was nothing but air. “You are shitting me.”

“I never lie,” Ronan said. He frowned disbelievingly. This felt like a more bizarre scenario than anything that had happened to this point. “Wait. You thought—it was never gonna be you and me. Is that what you thought?”

Kavinsky’s expression was scorched.

After this, when Kavinsky gifts him the dreamt Mitsu, the note he leaves reads: This one’s for you. Just the way you like it: fast and anonymous. Gansey blows past it with a comment on Kavinsky’s sexuality, but there’s real judgment in that joke—that Ronan used him like a dirty hookup and then went back home like nothing happened. It meant something to Kavinsky; it didn’t to Ronan.

Because ultimately, Kavinsky is a kid with a drug problem and a very bad family life who desperately wants Ronan—the person he sees as his potential partner, someone to be real with, maybe the only someone for that—to give a shit about him. “With me or against me” isn’t some sort of grand villain’s statement, it’s a codependent and wounded lashing out in the face of rejection. If he can’t have the relationship he wants, he’ll take being impossible to ignore instead. It’s also worse than simple rejection: it’s that Kavinsky has given himself to Ronan, has been open and real with him, has been intimate with him—and Ronan uses him then leaves.

To be clear, I don’t intend to justify his ensuing actions—they’re flat out abusive, and intentionally so—but I do think it deserves to be noted that Ronan does treat him with a remarkably callous disregard. Perhaps it’s because he doesn’t see how much Kavinsky is attached to him. Or, more accurately, neither one of them are capable of communicating in a productive or direct fashion about their attraction to each other; it’s all aggression and avoidance and lashing out. Perhaps it’s because he thinks there’s going to still be a future where he can balance both Kavinsky and Gansey in different halves of his life.

Except he’s wrong about that, and he pushed too far, took too much, and broke the one thing left that was keeping Kavinsky tethered to bothering to be alive. Kavinsky kills himself to make it a grand fucking show, and he does it to be sure Ronan knows he’s the reason. Which is, again, wrong—deeply, deeply wrong; it isn’t Ronan’s responsibility to make anyone else’s life worth living—but also real and tragic and awful. This all comes out in their confrontation in the dreaming forest of Cabeswater, when Ronan tries to convince Kavinsky that there’s no reason to do this—that life’s plenty worth living, et cetera.

“What’s here, K? Nothing! No one!”

“Just us.”

There was a heavy understanding in that statement, amplified by the dream. I know what you are, Kavinsky had said.

“That’s not enough,” Ronan replied.

“Do not say Dick Gansey, man. Do not say it. He is never going to be with you. And don’t tell me you don’t swing that way, man. I’m in your head.”

The implication being, of course, that Kavinsky could be with him. Ronan even has a moment, there, together, where he thinks about how much it has mattered to have Kavinsky around in his life, but it’s too late. He’s dead shortly thereafter, going out on the line, “The world’s a nightmare.” It’s the tragic arc at the center of The Dream Thieves—the titular one, in fact. This is a novel about Ronan and Kavinsky, and the things Ronan knows about himself at the close of the book. I’ve seen some folks argue that they think Kavinsky is a sort of mirror for Ronan himself, but I’d disagree: if anything, he’s a dark mirror of the things Ronan wants, the things he loves. He’s the opposite side of the coin from Adam and Gansey. He offers Ronan an equal sort of belonging, except in the “black place just outside of the glow.” Bonus round: he died thinking that no one human being believed he was worth a damn, after Ronan used him and left him.

It doesn’t excuse anything he does, but it gives everything a hell of a lot of aching depth.

Also, one further point of consideration: as readers, it is simple to identify with Gansey and see Kavinsky as worthless, as bad for Ronan, et cetera. (The substance party scene and aftermath are spectacular characterization for Gansey as someone who is capable of fire and cruelty and callousness, while he also feels overwhelming affection for Ronan at the same time.) However—Kavinsky thinks Gansey is bad for Ronan. From his perspective, Gansey is holding Ronan back from being the person who he most is at heart; he sees it as a codependent and controlling relationship, and he hates it, because he doesn’t appreciate seeing Ronan Lynch on a leash. He sees Gansey’s control as belittling and unnecessary, paternalistic. It’s rather clear—the scene with the first incorrectly-dreamed Camaro, for example—that he thinks Gansey doesn’t appreciate Ronan enough, that he would do better by him, treat him how he deserves to be treated.

Of course, he isn’t asking Ronan’s opinion about that—and he is firmly not a good person; if nothing else, his blatant disrespect for consent alone is a massive issue. But there’s a whole world in Kavinsky’s brashness and silences and horrible efforts at honesty, attraction, something close to obsession or devotion. It’s subtle, but it’s there, and it enriches the whole experience of The Dream Thieves to pay close attention to it. It’s Kavinsky’s suicide that drives Ronan to the significant moment where he admits that he “was suddenly unbearably glad to see Gansey and Blue joining him. For some reason, although he had arrived with them, he felt as if he had been alone for a very long time, and now no longer was.” He also, immediately, tells Matthew that he’s going to divulge all of their father’s secrets. Because no longer hates or fears himself or the secrets inside him.

I’ve also glossed over a significant portion of the text, though, in digging into this one specific thing. It’s just a specific thing that strikes me as unique about this novel, and is another example of the rewards the Cycle offers for reading closely, reading deeply, and paying very close attention to every bit of prose. Stiefvater, as I’ve said before, balances a straightforward quest plot with an iceberg of emotional significance. The surface is handsome and compelling, but the harder you think the further you go, and it keeps on getting more productive.

A few further points, though: this is also the point at which it begins to become clear that this isn’t going to be a typical love triangle sort of thing. Noah and Blue’s intimacy, Gansey’s relationship with Ronan, the strange rough thing Adam and Ronan have between them, Blue and Adam’s falling out—this is a web of people, not a few clashing separate relationships. It’s got jealousy to go around between them all, too, something I found refreshing and realistic. So, on top of being a book about queerness and coming to terms with oneself, it’s also about the developing pile of humans that is the raven gang and their passion for each other as a group, rather than only as separate pairs or clumps.

Within the first fifteen pages comes one of the series’ most-referenced quotes:

“You incredible creature,” Gansey said. His delight was infectious and unconditional, broad as his grin. Adam tipped his head back to watch, something still and faraway around his eyes. Noah breathed woah, his palm still lifted as if waiting for the plane to return to it. And Ronan stood there with his hands on the controller and his gaze on the sky, not smiling, but not frowning, either. His eyes were frighteningly alive, the curve of his mouth savage and pleased. It suddenly didn’t seem at all surprising that he should be able to pull things from his dreams.

In that moment, Blue was a little in love with all of them. Their magic. Their quest. Their awfulness and strangeness. Her raven boys.

It doesn’t seem like much, but it’s the center-piece that is continually built upon: that there’s love here—and rivalry and passion and jealousy, too —but most intensely love. Also, on the second read, the way Stiefvater parallels Ronan and Blue is far more noticeable: from their reactions to Kavinsky, as the only two who seem actually familiar with him as a human outside of the context of his mythology, to their opposite but equal prickliness and readiness to go to bat for things, et cetera.

—but most intensely love. Also, on the second read, the way Stiefvater parallels Ronan and Blue is far more noticeable: from their reactions to Kavinsky, as the only two who seem actually familiar with him as a human outside of the context of his mythology, to their opposite but equal prickliness and readiness to go to bat for things, et cetera.

Adam is also a heartbreaking wonder in this book. He’s trying to be his own man, too young and hurt and tired to do so on his own but unwilling to bend the knee to accept help from anyone either. He’s also coming to terms with his abuse and his own tendencies toward rage and lashing out—again, Kavinsky makes an interesting counterpoint to Adam in Ronan’s life and desires (see, for reference, the sex dream). Gansey’s passion for his friends and his inability to care for Adam in the way Adam needs to be cared for are illustrated spectacularly well, here.

To be honest, though Ronan is a focal point and the character I discussed most, each of the raven gang does a lot of unfolding and growing in this novel; it’s in painful bursts and clashes, but it’s all there. The plot, again, moves through some fascinating paces as well—the scene at the party, where the chant goes up about the raven king while Adam is falling apart under the pressure from Cabeswater, is chilling to say the least.

The thing about these books is: icebergs. The second read offers up a thousand-and-one brief snips of prose and implication and mountainous backstory that reward the careful eye, the thoughtful head, and the engaged heart. I’m having a great time going back through, let me just tell you.

The plot that The Dream Thieves sets up, though, comes to a head more directly in Blue Lily, Lily Blue—so that’s where we’ll head next, also.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.